Our Chronic Patient: the Healthcare System

Most chronic diseases are long-lasting conditions. They usually accompany the affected person for the rest of their life. The illness severely reduces quality of life, and it is the patient's responsibility to do everything to improve and maintain their condition. If they do nothing meaningful, do not change their eating habits, do not lose weight, do not cut back on alcohol, and do not increase physical and mental activity, there is nothing to be done — they are beyond saving. Our healthcare system is the chronic patient of our country. We have known this for decades.

In my opinion, our healthcare delivery system is a kind of chronic patient that does not receive proper treatment because its diagnosis was partly set up incorrectly and therefore it does not get the appropriate therapy, and partly because the patient (system) does not take its medicine and does not do everything to recover. It is therefore not surprising that its "condition" continuously deteriorates.

The government provides significantly fewer resources than necessary to solve the worsening crisis of the healthcare system. It is as if they do not take the problem seriously.

The determination of the causes leading to today's situation is (partly) mistaken, which also misleads the definition of necessary actions. It is a grave error to treat the problems primarily as financial questions instead of analyzing structural problems.

To define the disease of Hungarian healthcare and to arrive at a correct diagnosis, we must indeed go back to the period before the world wars and analyze the initial conditions!

What can we not ignore?

Before the twentieth century, people's life prospects were determined by living conditions, nutrition, lack of protection against epidemics, and the primitiveness of medical procedures and remedies.

Epidemics and diseases took their toll almost "without resistance." Even a hundred years ago, illnesses that are easily curable today were often fatal.

For centuries, human communities established hospitals and later modern hospitals to isolate and treat patients. However, because of the lack of effective therapeutic options, mortality rates in these institutions —even in the 1890s— exceeded 90% (London hospitals, Komesaroff 1999), meaning that until the end of the 19th century people went to hospitals to die (Healy & McKee 2002)! In the absence of effective procedures and remedies, hospital care was defined until the 1950s by long inpatient stays and conservative treatment.

Our hospital buildings have an average age of over 70 years; more than a third were built before 1945, and nearly 50% were built between 1950 and 1985. In other words, we built our hospitals when medical technology was exhausted by the stethoscope, the spatula and the reassuring words of the doctor.

Our hospitals were built close to each other because at that time a one-day travel distance by cart was only about 30–40 km. This created a large number of hospital buildings which have since been clung to tooth and nail.

The hospital structure does not take into account that our daily living conditions and technical-technological environment have radically changed over the past half century.

Think of the technological developments of the last century: the rise of computers, the Internet, mobile phones, mass communication, changes in road and air transport, and the structure of commerce. Similar-paced development occurred in healthcare as well.

A host of new diagnostic and therapeutic tools, techniques and procedures —antibiotics, a multitude of drugs— help our survival; vaccines prevent epidemics; advanced infection control is applied, and more. Due to these factors, life prospects have improved significantly, life expectancy has increased, and by 2020 the proportion of those over 65 is expected to exceed 20% of the total population (while the number of people supporting them decreases).

Meanwhile, the pattern of diseases has also changed: many illnesses that were of great importance 50–100 years ago are now rarely seen, while chronic diseases and their combinations come to the fore over long lives. Diabetes, hypertension and generally vascular diseases, cancers, osteoporosis, dementia, etc., constitute the main tasks.

However, the care for these conditions no longer requires the healthcare structure and care logic of previous centuries. Modern therapeutic procedures generally do not require hospital stays lasting weeks; consequently, there is no need for gargantuan hospitals with hundreds of beds. Thanks to the development of diagnostic and therapeutic tools, surgical techniques and procedures, drugs, infrastructure (road network, telephone coverage), supporting industries (ambulance services, medical remote monitoring), and IT (decision support, telemedicine), access to a doctor and diagnosis can be significantly shortened, the duration of care reduced, same-day procedures and home care become feasible and safe, and economic management becomes controllable. Definitive care tends toward outpatient and primary care.

Hungary's "ageing" hospital system should face the challenges posed by increased life expectancy and the growing proportion of elderly people. One of its greatest problems (in addition to those already listed) is decades-long stagnation and the persistent disregard of the above processes. Due to faulty structure, disorganization, solving tasks in the wrong place with inappropriate tools, and the lack of motivation among stakeholders, the entire delivery system is in crisis.

Hospitals should also meet the increased public and political expectations resulting from free access to information. Today, descriptions of diseases and diagnostic and therapeutic options are freely available on the Internet and elsewhere, so some patients know their options better than the doctor and expect them to be provided (cf. Health Act). Due to changes in general living standards, 6–8-bed common hospital wards (as an offering) do not meet the expectations of patients (and their relatives). Better care conditions and advanced diagnostics and therapy, however, cause rapidly rising costs.

According to WHO data from 2008, the hospital sector absorbs 35–70% of all resources that nations can spend on healthcare. It is therefore an extremely costly system element to maintain. The national budget included nearly HUF 400 billion to cover the costs of the domestic inpatient (and outpatient) care system, with more than 70% of that sum covering wages and contributions, while the remaining approximately HUF 100–120 billion serves energy, water-sewer, food services, cleaning, security, laboratory materials, surgical supplies, procurement of new devices and technologies, drugs, building renovations, maintenance and repairs of equipment, etc.

However, this amount is clearly and evidently insufficient. Institutional performance must be artificially kept in check. In recent years, several times (typically at year-end) tens of billions above the budget pumped into the system have been "absorbed without trace" by the system. According to institutions' own reports, unpaid bills accumulated with medical suppliers amount to several tens of billions of forints, though suppliers believe it may exceed that. Despite this huge additional "financing," every institution extensively applies austerity measures —a practice based on flawed reasoning and a short-sighted strategy.

"Savings" are attempted by postponing renovations, equipment renewal, maintenance and repairs and by cutting on patient safety, which causes buildings and equipment to deteriorate faster and raises complication rates. The average age of our hospitals' medical devices is currently 15–20 years, which is very unfavorable, especially considering that the obsolescence period for medical-technology devices is 8–10 years. This seemingly short period is actually long compared to other surrounding technologies. Think of replacement cycles for our cars, mobile phones, TVs or computers. The technical "decay" and obsolescence of our institutions are a "time bomb" ticking over us and jeopardize the population's care safety. Replacing machines with ones appropriate to the era requires an astonishing amount of resources.

Despite the budget's large share spent on wages, we must not forget that in recent years the outflow of human resources from the system has been accelerating. The main reason is that Western European institutions offer up to 5–10 times higher incomes, while the working environment is incomparably more favorable than at home.

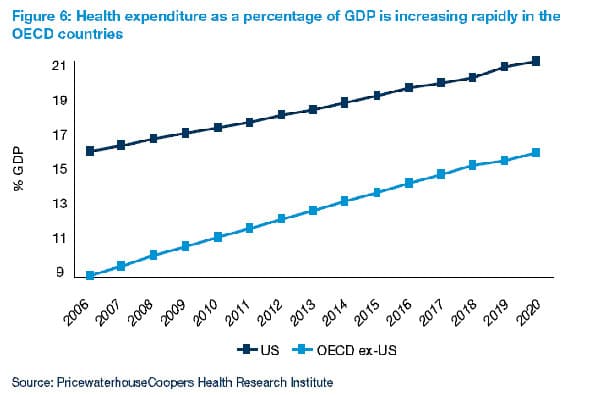

The health expenditures of various OECD countries as a percentage of GDP are rapidly increasing. Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Research Institute, 2010

It seems that for the highest-level decision-makers it is still not clear what magnitude of problem they face, or how much damage the delay in system-level intervention causes to Hungary's future.

The global economic crisis has strengthened initiatives worldwide that wish to end the procrastinating strategies that postpone healthcare system reorganization and to face the responsibility we owe to future generations.

Several factors can increase the chances of avoiding collapse, but we must change our attitude toward the healthcare system. Without a change of strategy, the current system will be driven into crisis by its excessive size, disorganization, inability to renew technologically and managerially, and its feudal relations.

Due to changes affecting our country's population, it is time to ask ourselves:

- What kind of healthcare do we want for ourselves in 2025, and what do we think about 2050?

- How healthy a society do we want and how healthy can we afford to be?

Once we decide, we must direct resources to serve these goals. The central, decisive, strategy-driven use of these resources is the path out.

From previous governments' actions we have seen that isolating and closing certain elements of the structure while keeping others produced no meaningful results and even endangered public care. It sparked significant social discontent because the public rightly felt that hospital closures would leave them with no place to turn for care. Reform attempts that focused on isolated tasks instead of systemic thinking did more harm than good: even if an original problem was solved, the flawed approach caused other problems to surface and intensify.

From a purely technological standpoint, high-level healthcare for our population of 10 million could be solved with fewer than 20, but well-organized, inpatient care institutions —if they were located in a proper care hierarchy with precisely defined task distribution and uniform criteria.

The vast majority of our hospital buildings do not meet contemporary expectations and technological possibilities, and thus are not suitable for "continued use." A new structure is needed. Building so many institutions from Hungary's own resources would only happen over a hopelessly long period. We must, however, make use of European Union external funds. By allocating funds, we could build a new healthcare delivery system that simultaneously transforms the entire healthcare delivery network and the necessary background infrastructure (roads, emergency services, information technology, communication), placing it on a new development path that would determine the country's future and could serve as an international example.

However, the EU-funded developments to date do not represent progress; they conserve bad structures. In the absence of a central strategy, they are carried out in a way that enlarged buildings will demand higher operating and human resource costs. Specialist clinics have been placed where even a family doctor cannot be employed. Because granted support amounts were smaller than real needs, hospital monstrosities were built across the country.

We do spend the money, but the system will become neither better, nor more efficient, nor cheaper. We are wasting the pledge of our future pointlessly.

A nearby example: the building of the Klagenfurt hospital. It was not built a hundred years ago.

A review of the current "bring the hospital to the patient" principle is necessary: it is not the extremely expensive-to-maintain hospital that should be moved to the patient, but the patient should be transported efficiently, quickly and cheaply. Multiplying the size of the ambulance service would cost only a few of our hospitals' annual operating budgets. The placement of new institutions should be determined based on demographic and morbidity data, not local political interests.

The new institutions could be built in modern, energy-efficient buildings suitable for contemporary technologies, avoiding city centers where even ambulances cannot enter due to traffic jams.

Like a hotel or an office: the facade of Phoenix Children's Hospital, Arizona

Creating and building a smaller but more efficient institutional structure would have positive effects. Its opening would automatically close the old hospitals: who would cling to the crumbling-plastered, 8-bed ward, poorly equipped and poorly accessible old hospital once they see a new, modern and safe facility available?

The current shortage of doctors and nurses is partly virtual: they are scattered and almost disappear in the huge number of institutions we have. By concentrating the system, human resource coverage would improve. Instead of money being consumed by centuries-old, money-sucking buildings of the disappearing structure, funds would reach employees legally as wages, which would help stop emigration, restore professional prestige and enable effective action against under-the-table payments. Rebuilding the healthcare structure would boost the construction industry and affect employment. The advanced infrastructure realized around new institutions would also be an attractive settlement location for other industries.

A hospital does not need flaking plaster as an accessory! Interior spaces of Phoenix Children's Hospital, Arizona

Such a reorganization of the healthcare system would also significantly raise our country's international prestige, since healthcare systems worldwide struggle with similar problems.

A value-creation-based structural change in healthcare could stop our country's slide to the tail of the region. The consistent implementation of a forward-looking concept would be sufficient on its own to strengthen international confidence and convince investors. The positive image (and real capability) of a small, high-technology system could attract research and development projects that have so far not settled here due to current technical limitations. Improved international perception of our healthcare system would provide a real basis for exploiting opportunities in health tourism as well.

A patient room in Phoenix Children's Hospital (Arizona). Like in a hotel.

Supplement: This article of mine is rather old. Between 2006 and 2012, as co-chair of the Medical Technology Association, I gave several presentations on this topic at medical and hospital management conferences. I summarized what was said there in 2014. It has not lost its relevance, although of course many things have changed since the article was written.