Rehabilitation of Peroneal Nerve Palsy

Peroneal nerve palsy can result from damage to either the central or peripheral nervous system, although peripheral causes are more frequent. The condition primarily affects the common peroneal nerve, which branches from the sciatic nerve and runs around the fibular head, making it particularly vulnerable due to its superficial location and anatomical course.

Peripheral causes of peroneal nerve palsy

The most common peripheral causes of peroneal nerve palsy include direct injury (trauma) to the nerve or prolonged compression at the fibular head. Compression can be caused by seemingly innocuous situations: for example, falling asleep on a chair at a party with your legs crossed while a bit tipsy — you may wake up with a palsy. A tight cast or the edge of a bandage can cause a similar problem.

Surgical procedures, especially those involving the knee or lower leg, can also cause iatrogenic (treatment-related) nerve injury. Retractors or forceps used during surgery can press on the nerve.

Central causes of peroneal nerve palsy

Less commonly, central nervous system disorders can produce peroneal-like dysfunction.

Stroke, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injuries affecting the L4–S1 segments can present with symptoms similar to peripheral peroneal palsy. However, these central causes typically come with additional neurological signs and often affect multiple nerve distributions.

Symptoms of peroneal nerve palsy

The characteristic appearance of peroneal nerve palsy is a "dropped" foot, marked by inability to dorsiflex the foot and extend the toes.

As a result, when walking the toes do not lift off the ground, so the affected person swings the foot forward in an arc-like, lateral "fling." The gait appears "duck-like" and uneven. The hip must be lifted, causing side-to-side trunk sway and placing strain on the hips and spine.

Sensory disturbances can also occur, especially on the dorsum of the foot and the lateral aspect of the lower leg.

Diagnosis

An accurate diagnosis requires a thorough clinical examination, including muscle strength testing, sensory and reflex assessment. Electrodiagnostic tests, such as nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG), play a key role in confirming the diagnosis, locating the lesion and determining the severity of nerve damage.

Treatment of peroneal nerve palsy

The first step in treatment is addressing the underlying cause, particularly relieving any compression. Tight casts or dressings must be removed and space-occupying lesions treated. These interventions prevent further complications.

Treatment has two pillars: electrotherapy (denervated stimulation) and physiotherapy (exercise therapy).

Denervated muscle stimulation

Contraction is essential for muscle viability. The impulse for contraction is sent from the brain through the spinal cord and motor nerve terminals (the latter being the muscle-nerve junction). If this communication pathway is interrupted, the muscle receives no contraction signals and begins to atrophy rapidly. Because nerve regeneration is slow, if the muscle does not contract for months it undergoes irreversible remodeling, degenerates and the palsy may become permanent.

The impulse delivered by an electrostimulator device causes the muscle to contract just as a signal from the brain would. Contraction is vital to maintain muscle health, strength and mass.

Consequently, electrical stimulation is an indispensable part of treating peroneal nerve palsy because it helps prevent muscle atrophy, maintains local blood flow and may promote nerve regeneration.

Nerve healing and regeneration is a very slow process and always starts from the origin. Current understanding suggests nerve fibers grow only a few tenths of a millimeter per day, at best up to 1 mm per day. The peroneal nerve may start 60–80 cm from the spine. That means months may pass before the regenerating nerve once again "reaches the muscle."

The muscle cannot withstand so long without stimulation. If it does not receive stimulation and cannot contract, within one and a half to two years muscle tissue will be replaced by connective tissue and, even if the nerve regenerates, the muscle will be nonfunctional and the palsy will persist.

Therefore, during the lengthy recovery from palsy the most important measure is persistent stimulation to maintain the muscle in a functional state, even though for 1–2 years there may seem to be no visible "result."

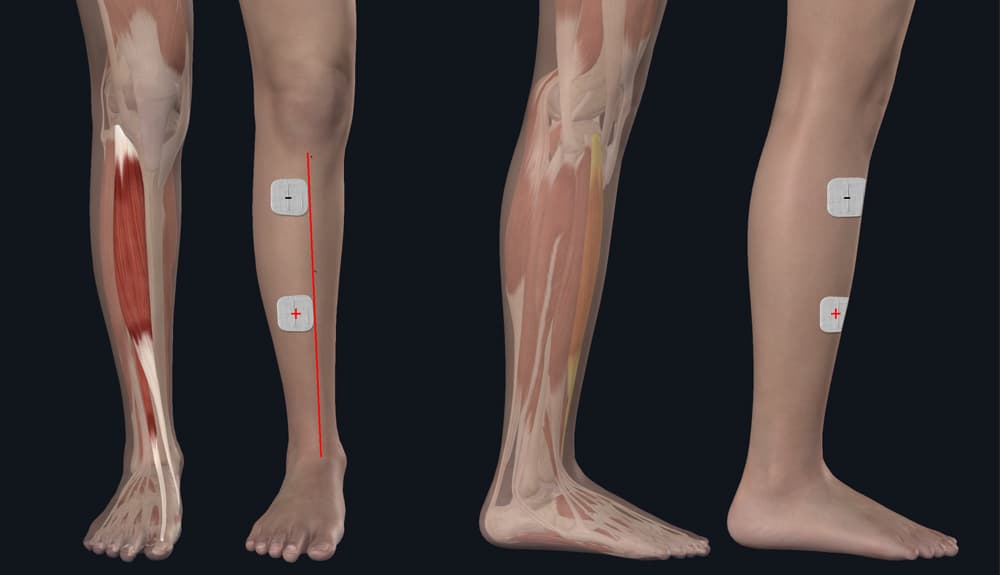

Electrode placement guide

This illustration shows which muscle we are talking about. Peroneal palsy affects the muscles on the anterolateral surface of the shin (especially the tibialis anterior muscle).

To locate the electrode positions, palpate along the anterior edge of your shin bone (I marked it with a red line). Place the first electrode about 5–8 cm below your kneecap over the muscle. The inner edge of this electrode should touch the shin bone edge and extend outward from it. Connect the negative pole of the cable to this electrode.

Place the other electrode lower on the muscle, approximately at mid-shin level or slightly below. Connect the positive pole to this electrode.

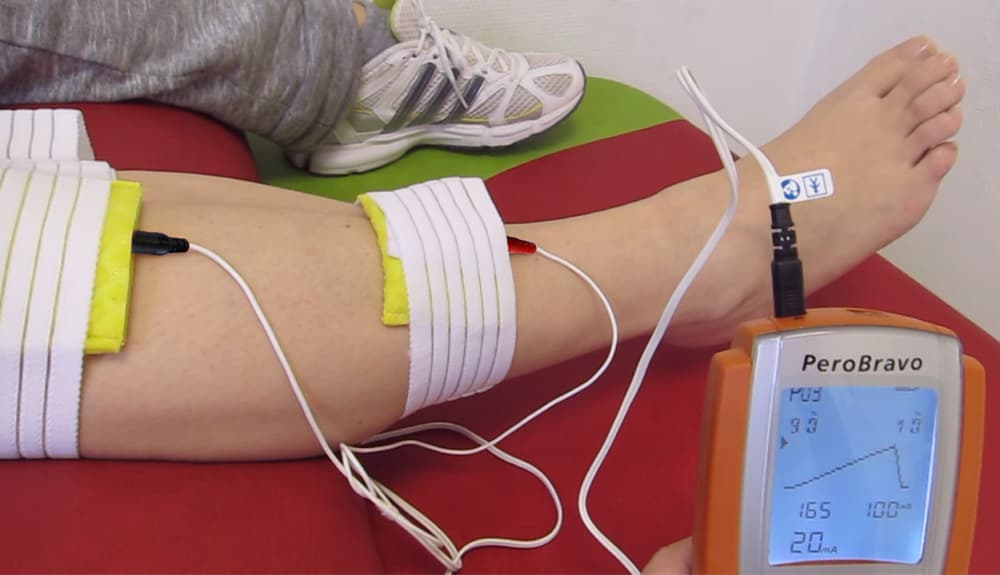

If you use rubber electrodes with a sponge instead of self-adhesive electrodes, the picture shows the former: a wet sponge in a cover secured with an elastic strap.

The form, duration and rise time of the denervated pulse should be adjusted depending on the severity of the lesion!

In severe peripheral nerve damage, start with triangular pulses of 300–900 milliseconds. If the device allows it, begin with a rise/fall ratio of 90%/10%. The PeroBravo device has such a setting option.

If the nerve damage is moderately severe, then triangular pulses or nearly one-second pulses will be too long and too intense for the nerve, causing an unpleasant stimulation sensation. For moderately severe injuries, therefore, a trapezoidal pulse is recommended rather than triangular.

As nerve regeneration improves, long-duration (100–300 ms) square waves may become appropriate.

If the muscle responds well to denervated square pulses, that indicates the nerve damage is moderate. This offers the best chance for regeneration. Naturally, the more severe the damage, the longer the regeneration time and the lower the chance of full recovery.

How can you tell which pulse is correct?

There are two methods. One is to try the programs one by one (don't worry — none of them will harm you, at worst you'll just feel it's not the right one). After a few minutes of trial you will find the suitable setting.

The other method is provided by the device itself (PeroBravo, Genesy 1500, Genesy 3000) for your physiotherapist. This helps determine the most appropriate pulse/duration. These tests are usually performed by clinic professionals. If you don't get help from a physiotherapist, the first method (trial and error) will generally give you the same result.

Exercise therapy and therapeutic exercises

Exercise therapy is the other cornerstone of peroneal nerve palsy rehabilitation!

Regular movement helps maintain joint mobility, prevent contractures and promote correct muscle activation patterns. Exercises should address dorsiflexion (lifting the foot), "plantar flexion"/standing on tiptoe, and rotational movements. In the beginning exercises may be passive, then active-assisted, and finally active movements as nerve function returns.

Balance and proprioceptive exercises gain increasing emphasis as recovery progresses. They help re-establish normal movement patterns and improve functional stability during walking and other activities.

Special attention must be paid to gait mechanics. Initially compensatory strategies are needed. Later, as nerve regeneration proceeds, focus more on heel strike, foot clearance during the swing phase and overall gait efficiency.

Physiotherapy combined with electrical stimulation provides the best chance of recovery.

Expected recovery time

Recovery from peroneal nerve palsy varies. Mild compression injuries can recover within weeks to months. More severe injuries may require 6–12 months and even with optimal treatment residual symptoms can remain.

Role of orthoses

Ankle-foot orthoses are often recommended for people with foot drop. While these devices help prevent falls, improve walking efficiency and maintain proper joint alignment, I do not recommend wearing them constantly. The reason is that the muscle held by the orthosis quickly loses strength and mass. Constant use of an orthosis can therefore impair the chance of recovery. However, as I mentioned, they can be important when you need to go out — they help keep walking safe. But do not use them at home or during practice. Active movement is necessary to regain muscle strength and function.